Prior to the talk, the following notice appeared on the web site of the British Isles Family History Society of Greater Ottawa:

The fact that any of us are here today is a miracle. Take the sad case of Gail Roger’s great-grandfather, Alexander Roger — the sole child of his parents to have offspring — who, by the time he was 41, had lost every one of his five siblings, for reasons ranging from tuberculosis, to drowning in the South Pacific, to laudanum, to cirrhosis of the liver. This tale will meander from Carse of Gowrie in Scotland to Battersea Park south of the Thames, with a couple of nods to Sherlock Holmes and a very, very indirect connection to Jack the Ripper. Oh yes, and there was a scandal. In Battersea.

About the Speaker

This is the fourth of Gail Roger’s presentations for BIFHSGO which, she likes to pretend, are for the edification and entertainment of her fellow family historians. The real, self-serving reason is that each presentation gives her own research a needed kick in the butt. Although not a Sherlock Holmes fan per se, Gail often falls into reveries of the WWSD (What Would Sherlock Do?) variety.

I want to begin this presentation with a solemn pledge: I will not be singing. The last time I did a talk for BIFHSGO, I did break out into song occasionally. The fire alarm in Library and Archives went off and everyone was driven out into the freezing rain.

I feel directly responsible, and I'm sorry.

This story concerns my side of the family, but I must confess that the real Sherlock Holmes fan in our house is my husband. He's also a fan of Oscar Wilde and Aubrey Beardsley.

I married him anyway.

For myself, I've never been a particular fan of mystery and detective novels; I read them if I like the author, or if they've been recommended to me.

So, a year or so ago, upon a recommendation by Lost Cousins, I was reading a trio of novels by Steve Robinson who writes crime mysteries featuring a professional genealogist named Jefferson Tayte. Tayte is American (obviously), but he regularly finds himself in mortal peril in England because apparently everyone there wants to kill genealogists.

The books are reasonably entertaining, easy reads. And I noticed that Jefferson Tayte is fond of quoting - misquoting actually - Sherlock Holmes.

I found myself wondering how much of Holmes' technique fits in well with genealogical research:

When you have eliminated all which is impossible, then whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth. - The Blanched Soldier

(This is a very famous quote that is misquoted several times by Jefferson Tayte. Maybe that's why people keep trying to kill him.)

There is nothing like first-hand evidence. - A Study in Scarlet

It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts. - A Scandal in Bohemia

There is nothing more deceptive than an obvious fact. - The Bascombe Valley Mystery

"They say that genius is an infinite capacity for taking pains," he remarked with a smile. "It's a very bad definition, but it does apply to detective work." - A Study in Scarlet

(Just to be clear, I am in no way claiming to be a genius.)

It has long been an axiom of mine that the little things are infinitely the most important. - A Case of Identity

Nothing clears up a case so much as stating it to another person. - Silver Blaze

The last one is my personal favourite and the reason for this presentation. I'm using you.

Actually, reading through these feels a bit like a series of bludgeons to me, because these are all lessons in family research that I keep learning and relearning, over and over.

Today is February 13th, 2016. Exactly one hundred and twenty-six years ago, a young governess, who had recently lost her position, died from an overdose of laudanum, having poisoned herself before the horrified eyes of her mother. Sounds like a Victorian penny-dreadful, doesn't it? The young woman was my great-great-aunt Jessie Roger and her mother, my great-great-grandmother Elizabeth Roger née Davis. This was in 1890, the year before the first Sherlock Holmes short story "A Scandal in Bohemia" was published.

Other than that, the two things have absolutely nothing to do with each other.

I'll be giving you the details of that family tragedy later, but the awful thing is, it's only a fraction of the sad story of how my great-grandfather, the Reverend Alexander Roger, lost all five of his younger siblings and his parents by the time he was 43.

|

| Alexander Roger 1860 - 1933 |

No, he's not standing in a shower stall - it's a cleaned-up scan of a copy of a copy because I'm descended from the third child of the four children of Alexander Roger, but I suspect his siblings got all the family memorabilia.

My great-grandfather was a minister of the Free Church of England, which held to the belief that the actual Church of England wasn't nearly Protestant enough. In 1899, the South Wales Daily News described him as "the well-known anti-Romanist lecturer". My great-grandfather's one mention in The Times was in October 1902, when he was listed among the mourners for John Kensit, the founder of the Protestant Truth Society who got hit by a chisel thrown by a presumably Catholic protester, got blood poisoning, died, and was thus proclaimed a "Protestant martyr".

The Protestant Truth Society, by the way, is still around today. Its website makes for arresting reading.

There were several news articles about my great-grandfather - albeit not in The Times - written over a period of about twenty years; evidently he did a great deal of travelling and lecturing -- which may explain why he only had four children.

|

| http://search.findmypast.co.uk/search/british-newspapers |

In this article, published two years after Kensit's death, is a little taste of the views which guided my great-grandfather's life. I apologize in advance:

The Rev. Roger then delivered the lecture entitled "The Woman in Purple, Scarlet and Gold". He said that some of them might not like that appellation, but he hoped to show before the end of the series that Rome by her teachings and practices was directly opposed to the Gospel of the Grace of God. In dealing with that subject, he did not want to say anything that should wound the susceptibilities of his Roman Catholic fellow-countrymen. They were not fighting against persons, but against the system. . .

In an adjacent room an exhibition was held containing . . . fragments of human bones from the . . . Burning Place of the Inquisition in Madrid . . . replicas of the "iron maiden", the Spanish torture chair, the rack, and other hideous instruments of torture were also shown.

On Tuesday evening lectures were given by the Rev. Roger, one to children, and another on "The Black Popes and their subtle satellites". Wednesday evening was devoted to an exposure of "Convent Life: its customs and cruelties".

He sounds like a lot of fun, doesn't he? I can't help but wonder what the children's presentation was like.

|

| Cambridge Independent Press, 23 August 1901 Click on the image to enlarge it. |

Alexander wasn't always telling off those who weren't Protestant enough. He had a congregation to lead, christenings, funerals and weddings to perform, including this one, which happens to be for a distant relative of my husband. I was looking for something else - I'm always looking for something else - when I came across this society column and noticed that I recognized the bride's uncle, from one of my husband's ancestral villages, Braughing in Hertfordshire. I checked my online family tree and found the bride's name. She's my husband's fifth cousin twice removed.

My husband was very impressed!

Are you familiar with the Booth Poverty Map of London?

|

| Google Maps - clicking on the image will enlarge it. |

The Booth Poverty Map was a detailed colour-coded map assembled by the philanthropist Charles Booth which showed how affluent or poverty stricken the various neighbourhoods of London were. As the minister of the Emmanuel Free Church of England, Alexander was one of the scores of clergymen interviewed for the project.

As you can see, in 1900, his neighbourhood ranged from the reasonably comfortable, through the "well-to-do" to the out-and-out wealthy. I've marked the locations of his house and his church.

|

| You may click to enlarge. |

The Roger family wasn't always that comfortable and middle class.

He was right about that.

|

| My great-great-great-grandfather, great-great-grandfather, and great-grandfather |

It occurs to me that I'll be talking about three different Alexander Rogers, so I propose to refer to them as "Alexander the Voice Teacher", "Alexander the Gardener", and "Alexander the Minister" -- okay?

My father also said that the family came from Scotland - at some point.

This also turned out to be true. When I started my online research in 2002, one of my first stops was the FamilySearch transcription of the 1881 census -- because it was free. As first-timer research goes, it was somewhat of a windfall.

|

| The Roger family in the census, 3 April 1881, Battersea, Surrey |

This is my great-grandfather Alexander Roger the Minister as a young man, living with his parents Alexander Roger the Gardener and Elizabeth Roger née Davis plus two younger sisters in Battersea, which was then in the county of Surrey. (At this point, I didn't know three siblings were missing!) The elder Alexander is described as "Curate of Battersea Park". As an extra-special gift to a neophyte family researcher, here also is my great-great-great-grandmother Isabella, also born in Scotland!

Ah, the FamilySearch web site -- such a wonderful gateway drug....

My next step was to search for a christening record of an Alexander Roger born about 1825, with a mother named Isabella. There are a lot of Alexander Rogers in Scotland, but fortunately for me, not so many born in that time frame with a mother named Isabella.

FamilySearch also provided transcriptions of the Old Scottish Parish marriage records and, like the piece of an intricate puzzle, the only marriage that fit -- among rather a lot of marriages between an Alexander Roger and an Isabella -- was this one. Of course, what we're seeing here is the original parish entry, found much later, at Scotland's People:

All of which brought me to the tiny joint parish of Kilspindie and Rait.

I like Google Maps; they're uncluttered, you can work out distances between places (especially walking distances - these people didn't have cars), and you can create your own family history maps.

However, when I need a bit more detail as I close in, I use StreetMap.co.uk.

Kilspindie and Rait are halfway between the towns of Perth and Dundee.

Here, I've put squares around Dundee to the right, Kilspindie and Rait near the centre and Crieff to the extreme left because these are all places associated with my Roger family. Kilspindie and Rait are also among a number of small communities on the Carse of Gowrie.

However, when I need a bit more detail as I close in, I use StreetMap.co.uk.

Kilspindie and Rait are halfway between the towns of Perth and Dundee.

Here, I've put squares around Dundee to the right, Kilspindie and Rait near the centre and Crieff to the extreme left because these are all places associated with my Roger family. Kilspindie and Rait are also among a number of small communities on the Carse of Gowrie.

I've put a magenta line under the bit of the map reading "Carse of Gowrie", because it's difficult to read - also not that easy to pronounce. The Carse of Gowrie is about twenty miles long and about two to five miles wide, depending where you are.

"Carse" is a Scottish noun meaning a "fertile lowland beside a river".

Offhand, I can't think of an English noun meaning "fertile lowland beside a river".The closest I can come is "delta" or "watershed", which aren't the same.

The river in this case, is the River Tay, and - I'm sorry - I can't resist pointing out what's five miles north of Kilspindie. Can you see the red arrow in the above map?

That's Dusinane Hill. This year is the 400th anniversary of the death of William Shakespeare and I've seen a certain Scottish play several times where a king is threatened by Birnham Wood coming to Dusinane, and that's the Dusinane they're talking about. My ancestors would have known it.

Well, I find it thrilling, anyway...

Here's Kilspindie in the early 20th century, probably about a century after my great-great-grandfather Alexander the Gardener was born, but it was still tiny and remains tiny today. I suspect it hadn't changed much, although I gather the roads had improved since the 1790s, when they were described as very bad and narrow, as never sufficiently made, but now worse than ever . . . .

If you're researching Scottish ancestors, you may have encountered the Old and the New Statistical accounts of Scotland. If you've taken one of Chris Paton's online courses, you definitely have. They're detailed profiles of Scottish parishes, written by church ministers; the Old Account was published in the 1790s, the New Account in 1845. My folk had left Kilspindie by 1845, so here's an extract of the Old Statistical Account of the parish of Kilspindie and Rait in the 1790s, submitted by the Reverend Mr Anthony Dow who was the fellow who described the roads earlier:

Common people in the Carse are in general rather tall, strong and clumsy in person; dull, obstinate, rude and unmannerly.

Yes. These are my people.

Here's the even tinier parish of Rait, - its parish church was defunct and in ruins by the end of the eighteenth century. This photo was taken about three quarters of a century after the birth of Alexander the Gardener. I got these photos, by the way, from a book I encountered and purchased while doing my Pharos homework for Chris Paton's class.

As I've mentioned, Google Maps is great for showing you the walking distance between places,

but I find StreetMaps.co.uk is best for detail. I think it's safe to assume that there wasn't an antiques centre in Rait when my great-great-grandfather was born there in 1826.

So, if you've taken Chris Paton's courses on Scottish family research, you'll know to look for historical maps at the Scottish National Library web site. This one shows Fiery Knows, the farm where my great-great-great-grandmother Isabella Anderson - the mother of Alexander Roger the Gardener -- was born in 1793.

How do I know that Fiery Knows was the farm? Well, I confirmed it quite a bit later when I located Isabella Anderson's christening record, but I first learned of it from Chris Paton's course, once again when he directed us to search the Farm Horse Tax Rolls at Scotland's Places.

|

| Farm horse tax rolls 1797-1798 |

Here, for the tax rolls of 1797-1798 for the parish of Kilspindie, I learned that my great-great-great-great-grandfather James Anderson, of Fieryknows, was liable for taxes on two farm horses. (Four names above, we find our old friend, the Reverend Anthony Dow from the Statistical Account, and at the very end of the list, an Alexander Anderson at "Upper Fingask" -- a brother or cousin? I've yet to find out.)

Isabella was, so far as I know, the only daughter and the fourth of the five children of James Anderson - a tenant farmer - and Bithiah Anderson.

"Bithiah", which is a more common name than you'd think in 18th century Scotland, is an obscure Biblical name meaning "daughter of Jehovah". (I keep a name dictionary by the computer.)

The name Bithiah will figure in the story in a couple of minutes.

So when I finally got around to accessing the image of the original Kilspindie parish register of Alexander the Gardener's birth at Scotland's People, I learned that Alexander Rodger, the father of Alexander the Gardener, was a music teacher for voice, and thus I was confronted by one of the many mysteries of the Roger family. How on earth did Alexander the Voice Teacher manage to make a living in a tiny parish halfway between the towns of Perth and Dundee more than twenty years before there was a train available? Who was he teaching who could afford to pay him?

This is a guess. It is only a guess.

Fingask Castle, which has passed in and out the hands of the Threipland family over the past three and a half centuries, is a mile north of Rait, so it's possible that Alexander the Voice Teacher managed some clients from that direction. At some point, I'll have to hunt down the records for Fingask Castle. They are not, to my knowledge, online.

Another possibility is that Alexander the Voice Teacher and Isabella were planning to live in Crieff all along. It might have been less embarrassing to have their son Alexander in Rait, get married six weeks later, then move to Crieff.Fingask Castle, which has passed in and out the hands of the Threipland family over the past three and a half centuries, is a mile north of Rait, so it's possible that Alexander the Voice Teacher managed some clients from that direction. At some point, I'll have to hunt down the records for Fingask Castle. They are not, to my knowledge, online.

|

| Distance from Rait to Crieff, according to Google Maps |

"Alexander Rodger"- with or without the "d" in the middle - is not an unusual name in Scotland, and there are at least four candidates born at the right time in the parishes in between Crieff and Kilspindie. Furthermore, Alexander could have come from further afield, or he could have been considerably older - or even younger - than Isabella.

|

| Scotland's People web site http://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk |

At any rate, the christening record for their son Peter appears in the Crieff parish register in 1831 - five years after the birth of Alexander the Gardener. This is the sole piece of evidence I have for the existence of Peter.

Isabella was already 32 when she married Alexander the Voice Teacher, so that may explain the paucity of children. I have failed to find any other children aside from Alexander and Peter.

Then the whole family disappears.

Alexander the Voice Teacher and younger son Peter seem to have vanished forever -- I've been searching for them for the past 15 years in parish registers, censuses, and newspapers. Nothing yet.

|

| Original images of the Scottish censuses are available at http://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/ on a pay-per-view basis. Click to enlarge. |

Isabella reappears in the 1851 census, and following her through to the 1861 and 1871 Scottish Censuses, I learned she spent more than twenty years of her widowhood alone, working in the Dundee textile mills.

She's a "winder" in the 1851 and 1861 censuses, which is apparently "a person who transferred the yarn from bobbins onto cheeses or into balls ready for weaving", according to a now defunct web site about old occupations.

She would have been making about six to nine pence per week for sixty hours' work, according to the Friends of Dundee City Archives. This would be the rough equivalent of forty Canadian dollars today.

By 1871, when she was 77, she was a "stocking weaver", which I doubt was a promotion.

As we've seen, she did eventually go to live with her son Alexander the Gardener, because we saw her in the 1881 census in Battersea. She died in 1883 of old age.

But where was Alexander Roger the Gardener in 1841? I think I found him.

In the 1841 Scottish census, there's a 14-year-old Alexander Roger living with an Alexander Anderson and his family.

|

| Original images of the Scottish censuses are available at http://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/ on a pay-per-view basis. Click to enlarge. |

Remember that Isabella Roger née Anderson had a mother named Bithiah? - Bethia is a variant.

The eldest of Alexander's children in this census is the same age as Alexander Roger - James Anderson, who is a "Gardener's Apprentice".

My guess here - and I hope Sherlock Holmes would approve of my deduction - is that Alexander Anderson is Alexander Roger's maternal uncle -- there is an Alexander Anderson in the parish registers for Kilspindie, born in 1789 to the correct parents -- and that Alexander Roger, the future gardener, apprenticed with whomever his cousin James Anderson apprenticed.

By 1851, Alexander Anderson and his family had settled in Flintshire, Wales.

Alexander the Gardener had travelled the 425 miles to South Mimms, which, these days, is just within the ring that the M25 makes around Greater London. In those days, it was a small village fourteen miles from the City of London.

My guess here - and I hope Sherlock Holmes would approve of my deduction - is that Alexander Anderson is Alexander Roger's maternal uncle -- there is an Alexander Anderson in the parish registers for Kilspindie, born in 1789 to the correct parents -- and that Alexander Roger, the future gardener, apprenticed with whomever his cousin James Anderson apprenticed.

By 1851, Alexander Anderson and his family had settled in Flintshire, Wales.

Alexander the Gardener had travelled the 425 miles to South Mimms, which, these days, is just within the ring that the M25 makes around Greater London. In those days, it was a small village fourteen miles from the City of London.

|

| Remember to click to enlarge! |

This map is from a wonderful resource called A History of the County of Middlesex, which is available online at the website British History Online. If you have ancestors or lateral relatives living in what is now called Greater London during the past few centuries, this will give you a description and history of their neighbourhood.

|

| http://search.ancestry.co.uk/ Click to enlarge. |

I found Alexander the Gardener -- and he really is a gardener now -- living at a place called "High Stone". Like a good little family researcher, I checked his neighbours.

Not far away is another

Scotsman of Alexander's age who is a nursery foreman and since he has a journeyman gardener living with him, I'm guessing it's a not nursery for children. In between, there's a butler's wife.

I think we may be looking at people who work on the same estate. But which? I looked at neighbouring pages of the census, which were little help, except I knew that Alexander was not far from a place called Taylor's Lane.

This time, it was the less cluttered Google Map that was more of a help to me.

There's Taylor's Lane, right next to Hadley Highstone.

I enlarged the 1842 map to close in on the same area, and I don't know if you can make it out, but there's Old Fold Manor Farm, and the History of the County of Middlesex tells me that the Old Fold Manor had been around since the 13th century, and in the early part of the nineteenth century was still a sizeable estate. Was Alexander the Gardener working there? I think it's a reasonably good guess.

Eight years later, in 1859, Alexander the Gardener married Elizabeth Davis.

Here, we have a confirmation that I have the right Alexander: his father is listed as "Alexander Roger, Teacher of Music". (Oh, I love being right...)

This time, it was the less cluttered Google Map that was more of a help to me.

There's Taylor's Lane, right next to Hadley Highstone.

Eight years later, in 1859, Alexander the Gardener married Elizabeth Davis.

Here, we have a confirmation that I have the right Alexander: his father is listed as "Alexander Roger, Teacher of Music". (Oh, I love being right...)

|

| The Bayswater area today, with the location of the present St Matthew's and Hereford Road a few blocks to the northwest of the church. Google Map |

It confirmed that Bayswater changed beyond recognition in the middle of the nineteenth century. It started out as a semi-rural area, then, beginning in the 1840s, had a building boom.

Over less than two decades, fields disappeared, streets appeared and changed names, and the neighbourhood attracted residents described as "wealthy" and "merely well-to-do". I suspect such a neighbourhood would require the landscaping services of a young but experienced gardener, and that there would be plenty of openings for domestic servants.

I just want to give a quick rundown on the early life of Elizabeth, my great-great-grandmother, because what happens from here on in affects her deeply and mostly tragically.

|

| Google Map |

My great-great-grandmother Elizabeth Davis was born in Smethcott, Shropshire, probably in Smethcott Common where her parents appear in the censuses.

Perhaps you have seen the BBC Two factual television series Victorian Farm. That was filmed in Acton Scott, Shropshire, which is about eight miles south of Smethcott.

I was particularly interested in that series because Elizabeth Davis was the eldest daughter of a farmer - well, more likely an agricultural labourer, as I suspect they occupied one of the specially set aside "poor cottages" at Smethcott Common, which is a tiny place, even tinier than Kilspindie, or Rait.

Elizabeth was, according to the censuses between 1841 and 1901, born sometime between 1828 and 1833. Her age varies in every single census.

I do notice an unfortunate tendency to put down uncertain feminine ages to female vanity - this is usually said, with a patronizing chuckle, by male family researchers. I think Elizabeth may have genuinely not known when she was born, or she may have been born uncomfortably close to her parents' wedding in 1828, in which case she would have had something in common with her future husband. I can't find her in the 1841 census; I'm reasonably sure she had been sent out to work.

|

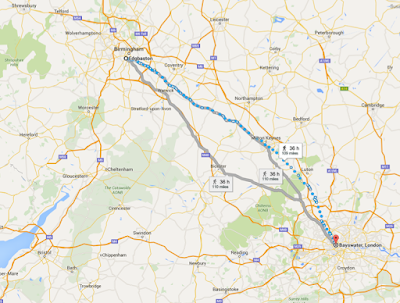

| Distance from Edgbaston to Bayswater, calculated by Google Maps. It is possible to click on the image to enlarge it. |

By the 1851 census, she was a young general domestic servant for a scale manufacturer in Edgbaston, Warwickshire, so sometime between 1851 and 1859, she had found her way to Bayswater.

By the following year, Alexander the Gardener and his new wife Elizabeth were in Buckinghamshire.

|

| Ordered through the General Register Office - https://www.gro.gov.uk/gro/content/certificates/ |

|

| Google Maps |

|

| Berry Hill House, circa 1948 - http://pulham.org.uk/2013/01/01/20-january-2013-berry-hill-buckinghamshire/ |

Mr John Noble, a leading varnish manufacturer, commissioned Robert Marnock, the famous Scottish garden designer, to 'beautify' his garden at Berry Hill, Taplow, near Maidenhead, towards the end of the 1850s.

(Yet another Scottish gardener! I'm beginning to think there was some kind of Scottish Gardening Mafia!)

Claude Hitchings quotes from an article that appeared in The Gardeners' Chronicle in 1860 (the same year Alexander the Minister was born):

The grounds are generally neatly managed, as far as effect is concerned, and the excellent state in which they are kept does credit to Mr Rogers, the gardener . . . .

Mr. Hitchings went on to state that "Mr Rogers later moved on to take over the job of Park Superintendent at Battersea Park . . . . " Another confirmation that this was the correct Alexander!

This was one of those Great Moments, so I did the prerequisite squawking and dancing in front of the computer.

My daughters hid upstairs.

I, of course, left a note on the post thanking Claude Hitching, and he replied in a charming email, inviting me to read more. While there doesn't seem to be anything else of relevance to me, there might be for someone here, so by all means, go and explore. Tell Mr. Hitchings I sent you.

I knew from the FreeBMD web site that Alexander the Gardener and Elizabeth went on to have five more children.

I also knew from the 1861 census and by his own birth certificate, that their second son was named Wilfred Edgar Roger. This is not a transcriber's mistake but an error in the original index, which is why it hasn't been changed.

|

| Ordered through the General Register Office - https://www.gro.gov.uk/gro/content/certificates/ |

There were now five Roger children, and here's the family in the 1871 census.

|

| 1871 English Census, Taplow, Buckinghamshire |

With four children. Who's missing? My ancestor, of course!

It took me a couple a years to find my great-grandfather, and I was initially puzzled when I did.

Here he is, Alexander Roger, 11 years old, from Taplow in a long list of boys ages 9 to 13.

Aha! They're pupils!

At first, all I could find online were brief descriptions of the school. This one is from an 1861 book entitled The Charities of London by Samuel Low Junior:

Bancroft's Hospital, Mile End Road, founded 1728, by F. Bancroft, who amassed a large fortune in the city. More than 100 boys are maintained and educated within the ages of 7 and 14. The appointment and control is in the Court of the Drapers' company, who present by rotation. Any poor boy between seven and 10 years of age is eligible for such presentation.

Bancroft Hospital is long gone, although there is an establishment across from where it used to be that is called the The Drapers Pub and Kitchen, which is a nice touch, don't you think?

This is how the school looked in the eighteenth century, probably about a hundred years before Alexander attended. Unfortunately, the name of the artist was chopped off at the web site, which turned out to belong to the present school which moved to Woodford, Essex in 1889 and seems to be quite posh today!

On the same web site, I found this:

I had had Dickensian visions of cruelty and starvation about Bancroft Hospital, but, looking at this, the boys seem to have been fed well and certainly kept very clean. I'm interested to see that the boys were instructed in the doctrine of the Church of England, given the religious path that Alexander's life took. It sounds on the whole, that this was a wonderful educational opportunity for him.

I wonder how this opportunity came about -- perhaps Alexander the Gardener made full use of his contacts working at fine houses (or in the Scottish Gardening Mafia).

I also wonder how the long separations affected Alexander the Minister's relationship with his brothers and sisters, to say nothing of his parents.

Through the Find My Past website, I came across a document that put where the Rogers were in the 1871 census in a whole new light.

Have you ever experienced what I call the "oops" document? That's when you get that birth or marriage or death certificate -- or will -- or whatever, and it disproves a good chunk of the research you've done on that family because the document reveals that you have the wrong person. Oops.

This is the polar opposite of an "oops" document. This is a proof of age for people applying for a job for the Civil Service. I found a transcription at Find My Past about five years ago and recently got an image of the original document.

Here, I have confirmation that my great-great-grandfather Alexander Roger was born in Kilspindie, the son of Alexander Roger "a teacher of music" and Isabella Anderson. There was much dancing in front of the computer that day.

I also danced a couple of years ago when my aunt sent me this via her granddaughter. It came with a mystery, of course: My cousin tells me that there was another photo.

She wrote: It looked like a staff or club photo, with 8 or 9 gentlemen and one lady named Miss Lewis. A.R. was in the same clothes as his portrait, and standing behind him is 'George Roger'. There wasn't a heading for the photo, just a name list, but as it was in such bad condition, I didn't take a copy for you. I'll have a look next time.

As of today, I have heard no further of this mystery picture, and have no idea who "George Roger" could be, despite many different kinds of searches. Based on my own experience, if I keep returning to the documents, I will find out eventually.

I'll let you know.

Here's the job Alexander was after.

From the transcription of the 1881 census all those years ago, I knew Alexander the Gardener was in charge of Battersea Park, but I didn't know that he was also in charge of Kennington Park, which is a bit to the west of Battersea.

Look at the date.

Alexander was appointed to his new position two weeks before the 1871 census was taken on April 2nd, so when the family was recorded in the census in Taplow, they were possibly already packing up for the move to Battersea, where they would be much closer to Alexander the Minister.

The family moved to Era House on Surrey Lane, steps away from Battersea Park. In 1871, they would have been surrounded by market gardens and plant nurseries, though I have to wonder what the air quality was like.

In this contemporary map, another beauty from the web site Mapco, you can see chemical works, turpentine works, saw mills, etc. lining the south bank of the Thames, less than half a mile away.

Public parks were still a relatively new concept. Battersea Park had opened in 1858, and not many decades earlier, the royal parks, such as Regent's Park, were only open to "a better class of people". Regent's Park, for example, charged admission to discourage lesser mortals, and Kensington Gardens was open to all who were "respectably dressed".

Perhaps Kensington Gardens was patrolled by fashion police.

Alexander was in charge of a new kind of park, meant for the health and enjoyment of all.

Even female cyclists. This is from the 1890s. Look at those mutton sleeves!

So, I found myself back where I began my research -- the 1881 census. But this time, I was looking at the original! Alexander the Gardener had now been in charge of Battersea Park for ten years.

Alexander the Minister wasn't a minister yet; he was a Commercial Traveller -- presumably a travelling salesman. Selling what? You got me.

Presumably not holy relics….

Florence was a florist's assistant, a respectable job. Jessie was at school.

I rather suspect that my great-great-great-grandmother Isabella joined the household not long after 1871, as this would have been the first time that her son Alexander was not living in servants' quarters.

Wilfred? I still didn't know what had become of him.

Cuthbert? Well, I did find him.

He was in training at Devonport Training School for Engineer Students, later Keyham College, later the Royal Naval Engineering College in Stoke Demerel, Devon.

The college was brand new; it had just opened the preceding year, which might explain why it looks particularly ship-shape here.

Another fine opportunity. I'll bet Alexander the Gardener was a proud dad.

A couple of months later, this notice appeared in the The Magazine of the Free Church of England.

Alexander the Minister really was a minister now, and he left London for nine years. I'll tell you how I know this in a few minutes.

Five years after the 1881 census, I found Alexander the Minister getting married in Cardiff to my Welsh great-grandmother - I do have several - Harriett Anne Probert.

Harriett, known as "Hattie" to her sisters, had several things in common with her new husband. Her mother had been in service in Edgbaston, like Alexander's mother. Harriett was also the eldest child in her family, and she too had been sent away to school, spending at least ten years at the Welsh School in Ashford, Middlesex which is just south of where Heathrow Airport is now, so she was far away from her family in Wales for a long time. The Welsh School, like Bancroft Hospital, started out as a British Charities school.

Looking at this record, two things leap out at me: first, it was witnessed by Harriet's youngest sister Louisa (signing here as "Louie"). Not long after, Louisa married, converting to Catholicism. I've often wondered how she and Alexander the Minister got along.

The other? A reminder that we shouldn't place all our faith in any document.

Harriet's father is recorded as a "Railway District Manager (deceased)". He was deceased, all right. My great-great-grandfather William Probert died horrifically when Harriett was six. The cattle train on which he was an under-guard collided with another train in Gloucestershire.

I guess Harriett didn't think anyone would check. She didn't count on her pesky great-granddaughter.

In the meantime, I finally found Wilfred!

I've had a subscription to Find My Past for a couple of years now - as an annual birthday present from my husband. (Thanks, honey.) During the years when I didn't, I would take advantage of their occasional Free Access weekends, entering familiar names, and this turned up.

No wonder I couldn't find him! He was at sea!

Then I found this:

and understood why I had failed repeatedly to find his death registration at FreeBMD.

I was reviewing this record a few days before the presentation - revisiting documents is always a good idea - and noticed something I had missed.

They're coordinates. I decided to try entering them into the search field at Google Maps.

I had a sickening feeling of lost-ness and desolation. I had to zoom out to see where Wilfred died.

In the middle of nowhere. Since the register said he was "supposed to have been swept overboard", then no one saw it happen.

We all die alone, but this is a particularly lonely way to die -- a world away from home in a vast expanse of stormy ocean.

The Register of Deaths of Masters and Seaman also lists the ship involved, so I decided to find out more about her.

The Jessie Readman carried passengers to and from New Zealand. An article in the Auckland Star dated November 21st, 1885 reported: The ship Jessie Readman, under the S. S. and A. company's flag, arrived in port this morning, and dropped anchor off the end of Queen-street Wharf. The vessel is in charge of Capt. Gibson, Mr Roger as chief officer . . . .

Once again, I needed an illustration for this presentation, so I began the search for images of the Jessie Readman.

They're not bad, but I wasn't inspired. That is, until I selected a photo, then glanced at the small "related images" at the bottom right-hand corner.

This is the polar opposite of an "oops" document. This is a proof of age for people applying for a job for the Civil Service. I found a transcription at Find My Past about five years ago and recently got an image of the original document.

Here, I have confirmation that my great-great-grandfather Alexander Roger was born in Kilspindie, the son of Alexander Roger "a teacher of music" and Isabella Anderson. There was much dancing in front of the computer that day.

I also danced a couple of years ago when my aunt sent me this via her granddaughter. It came with a mystery, of course: My cousin tells me that there was another photo.

She wrote: It looked like a staff or club photo, with 8 or 9 gentlemen and one lady named Miss Lewis. A.R. was in the same clothes as his portrait, and standing behind him is 'George Roger'. There wasn't a heading for the photo, just a name list, but as it was in such bad condition, I didn't take a copy for you. I'll have a look next time.

As of today, I have heard no further of this mystery picture, and have no idea who "George Roger" could be, despite many different kinds of searches. Based on my own experience, if I keep returning to the documents, I will find out eventually.

I'll let you know.

Here's the job Alexander was after.

From the transcription of the 1881 census all those years ago, I knew Alexander the Gardener was in charge of Battersea Park, but I didn't know that he was also in charge of Kennington Park, which is a bit to the west of Battersea.

Look at the date.

Alexander was appointed to his new position two weeks before the 1871 census was taken on April 2nd, so when the family was recorded in the census in Taplow, they were possibly already packing up for the move to Battersea, where they would be much closer to Alexander the Minister.

|

| Distance between old location of Bancroft Hospital and Era House calculated by Google Maps. You may click on the image to enlarge it. |

The family moved to Era House on Surrey Lane, steps away from Battersea Park. In 1871, they would have been surrounded by market gardens and plant nurseries, though I have to wonder what the air quality was like.

In this contemporary map, another beauty from the web site Mapco, you can see chemical works, turpentine works, saw mills, etc. lining the south bank of the Thames, less than half a mile away.

Public parks were still a relatively new concept. Battersea Park had opened in 1858, and not many decades earlier, the royal parks, such as Regent's Park, were only open to "a better class of people". Regent's Park, for example, charged admission to discourage lesser mortals, and Kensington Gardens was open to all who were "respectably dressed".

Perhaps Kensington Gardens was patrolled by fashion police.

Alexander was in charge of a new kind of park, meant for the health and enjoyment of all.

Even female cyclists. This is from the 1890s. Look at those mutton sleeves!

So, I found myself back where I began my research -- the 1881 census. But this time, I was looking at the original! Alexander the Gardener had now been in charge of Battersea Park for ten years.

Alexander the Minister wasn't a minister yet; he was a Commercial Traveller -- presumably a travelling salesman. Selling what? You got me.

Presumably not holy relics….

Florence was a florist's assistant, a respectable job. Jessie was at school.

I rather suspect that my great-great-great-grandmother Isabella joined the household not long after 1871, as this would have been the first time that her son Alexander was not living in servants' quarters.

Wilfred? I still didn't know what had become of him.

Cuthbert? Well, I did find him.

He was in training at Devonport Training School for Engineer Students, later Keyham College, later the Royal Naval Engineering College in Stoke Demerel, Devon.

The college was brand new; it had just opened the preceding year, which might explain why it looks particularly ship-shape here.

Another fine opportunity. I'll bet Alexander the Gardener was a proud dad.

A couple of months later, this notice appeared in the The Magazine of the Free Church of England.

Alexander the Minister really was a minister now, and he left London for nine years. I'll tell you how I know this in a few minutes.

Five years after the 1881 census, I found Alexander the Minister getting married in Cardiff to my Welsh great-grandmother - I do have several - Harriett Anne Probert.

|

| Ordered through the General Register Office - https://www.gro.gov.uk/gro/content/certificates/ |

Looking at this record, two things leap out at me: first, it was witnessed by Harriet's youngest sister Louisa (signing here as "Louie"). Not long after, Louisa married, converting to Catholicism. I've often wondered how she and Alexander the Minister got along.

The other? A reminder that we shouldn't place all our faith in any document.

Harriet's father is recorded as a "Railway District Manager (deceased)". He was deceased, all right. My great-great-grandfather William Probert died horrifically when Harriett was six. The cattle train on which he was an under-guard collided with another train in Gloucestershire.

I guess Harriett didn't think anyone would check. She didn't count on her pesky great-granddaughter.

In the meantime, I finally found Wilfred!

I've had a subscription to Find My Past for a couple of years now - as an annual birthday present from my husband. (Thanks, honey.) During the years when I didn't, I would take advantage of their occasional Free Access weekends, entering familiar names, and this turned up.

No wonder I couldn't find him! He was at sea!

Then I found this:

|

| Click to enlarge |

I was reviewing this record a few days before the presentation - revisiting documents is always a good idea - and noticed something I had missed.

In the middle of nowhere. Since the register said he was "supposed to have been swept overboard", then no one saw it happen.

We all die alone, but this is a particularly lonely way to die -- a world away from home in a vast expanse of stormy ocean.

The Register of Deaths of Masters and Seaman also lists the ship involved, so I decided to find out more about her.

The Jessie Readman carried passengers to and from New Zealand. An article in the Auckland Star dated November 21st, 1885 reported: The ship Jessie Readman, under the S. S. and A. company's flag, arrived in port this morning, and dropped anchor off the end of Queen-street Wharf. The vessel is in charge of Capt. Gibson, Mr Roger as chief officer . . . .

Once again, I needed an illustration for this presentation, so I began the search for images of the Jessie Readman.

They're not bad, but I wasn't inspired. That is, until I selected a photo, then glanced at the small "related images" at the bottom right-hand corner.

Have you ever done this? I clicked on "View More".

And there are a lot more pictures, most of them of the Jessie Readman. One of them, however, was markedly different.

And there are a lot more pictures, most of them of the Jessie Readman. One of them, however, was markedly different.

Wow. Isn't she beautiful? Now, I must ask you to notice the note I've attached to the bottom, which does not compromise the integrity of the image, and also please see that I have not cropped the image. That's what the instructions are at the National Library of New Zealand web site, and I am complying so I can share this photo with you. The National Library of New Zealand also notes that this picture is Dated from the Comber Index which indicates this ship visited Port Chalmers between 1870 and 1892.

Wilfred Edgar Roger died in 1886, two months after his brother Alexander married Harriett Anne Probert.

So one of these men could be my great-great-uncle Wilfred Edgar Roger, and I'd really rather remember him this way.

See? BIFHSGO presentations can engender multiple Great Moments in Genealogy!

Back in England, the Roger family continued to have gains and losses. On August 30th, 1888, Alexander the Minister and his wife Harriett welcomed the first of their four children, a daughter named Jessie, after Alexander's youngest surviving sister.

|

| You may click to enlarge the image. |

|

| A page from my online tree at Ancestry.co.uk |

While Elizabeth was in deep mourning, she could possibly take some comfort in the fact that all four of her remaining children were gainfully employed in respectable professions. Alexander the Minister was established in Cardiff. Cuthbert was an assistant engineer in the Royal Navy.

|

| Google Map - Mayfair and Belgravia, London |

Remember the Booth Poverty Map?

No poverty in this neighbourhood, and Hyde Park Square is coded yellow, meaning out-and-out bags of money.

|

| A recent Google Maps Street View of Hyde Park Square |

A governess was of higher rank than the household servants in such a posh place, so it was a good job for a middle class girl who had to work, as Jessie probably did after the death of her father.

I knew something was up with Jessie when her name turned up on the now-defunct Black Sheep Index years ago. Anyone remember this site?

I knew Jessie had died young because of her death registration, but my great-great-grandfather William Probert -the one who died in the train accident, and was Alexander the Minister's late father-in-law - appeared on the Black Sheep Index under Railway Deaths. Jessie was on the "Black and White Sheep" list, so I assumed she'd had an accident. I never got around to sending for her file, mainly because it's getting increasingly difficult to explain the concept of a money order to postal clerks and bank clerks.

Eventually, I ordered up Jessie's death certificate from the General Register Office.

It was a bit of shock.

I was also startled to note the name of the coroner.

Any woman who has given birth would do a double-take. It turns out that this is Athelstan Braxton Hicks -- it was his father John Braxton Hicks who gave his name to false labour contractions. Athelstan, as you can see here, was the Coroner for London and a couple of years previous, he had officiated at the inquest of at least one of the victims of Jack the Ripper.

Here's what I've been able to piece together about the week during which Jessie Roger's young life fell apart.

On February 5th, 1890, Jessie Roger lost her position as governess at 18 Hyde Park Square - which, incidentally, is a fifteen-minute walk from 22 Baker Street and where the Sherlock Holmes Museum is today. No connection to this story, of course; it's just a neat coincidence.

Jessie did not tell her family of the termination, but left home as usual each morning.

One of the places she did go to was the home of a Mr Willis, a dentist and married man who, at one point, had been warned away from Jessie's sister Florence, probably by her brother Alexander, not that this appeared to make any difference. Jessie visited Mr Willis twice this week, asking him to draft letters to her former employer and to a governess agency on Harley Street.

On the second visit, which was February 12th, he thought she appeared intoxicated, and invited her to stay and recover while he went out. When he returned, she had gone. He never saw her alive again.

Here's what I've been able to piece together about the week during which Jessie Roger's young life fell apart.

On February 5th, 1890, Jessie Roger lost her position as governess at 18 Hyde Park Square - which, incidentally, is a fifteen-minute walk from 22 Baker Street and where the Sherlock Holmes Museum is today. No connection to this story, of course; it's just a neat coincidence.

Jessie did not tell her family of the termination, but left home as usual each morning.

One of the places she did go to was the home of a Mr Willis, a dentist and married man who, at one point, had been warned away from Jessie's sister Florence, probably by her brother Alexander, not that this appeared to make any difference. Jessie visited Mr Willis twice this week, asking him to draft letters to her former employer and to a governess agency on Harley Street.

On the second visit, which was February 12th, he thought she appeared intoxicated, and invited her to stay and recover while he went out. When he returned, she had gone. He never saw her alive again.

During that day of February 12th, Jessie visited her sister Florence, and two chemists to buy rather a lot of laudanum. The first chemist refused, because of "her peculiar manner". The second chemist sold her "sixpenny-worth of laudanum for neuralgia" because she seemed "a fine young woman, and of good address, and appeared to him to be really suffering in the way described."

Laudanum is a mixture of opium derivatives and alcohol, and was a common item in many Victorian homes for medicinal purposes. In fact, it was recommended for helping babies to sleep! It can be, of course, addictive, and, taken in large enough amounts, poisonous.

That evening, Jessie returned home. Her mother confronted her because she seemed intoxicated and agitated, demanding to know where she had been. Jessie finally cried: "I will tell you! I have been walking about, and now I am going to do it!" With that she downed a vial of laudanum and rushed from the house.

|

| Jessie Roger's final outing |

She had arranged to meet her fiancé Arthur James Oakman, a mercantile sailor home on leave. Walking a few blocks from her house, Oakman saw that she was unsteady and he also accused her of drinking. When she said she'd taken laudanum "to drive away the pain", he didn't understand the severity of the situation and continued with her toward a landmark called Albert Palace, about a fifteen-minute walk, as she steadily got worse. By the time he got her turned around, she was practically unable to stand, and he had to carry her from Bridge Road to her house in Surrey Lane.

The same doctor who signed Jessie's father's death certificate was called. It was no good. Jessie died about 4 a.m. the next day.

Well, the papers were very interested.

I got the basic story from the detailed and sometimes contradictory reports in Lloyd's Weekly Newspaper, The Daily News (at one time owned and published by another of my great-great-grandfathers), The Illustrated Police News (no pictures, but plenty of verbatim quotes), and The Manchester Chronicle.

The last time I checked the British Newspaper Archive at Find My Past, there were articles about Jessie's inquest in half a dozen London papers and twenty-six more papers across the United Kingdom! This number changes as the archives are updated.

It was a sensational story: a young girl, sister to a clergyman, daughter of a park superintendent, described by her mother as "a strong girl, mentally clever, quick and clear". There was her young man, her strange indefinable relationship with a married man, her depression following the recent deaths in the family --- and her drinking. Florence Roger admitted that she and her sister both "were in the habit of taking spirits".

It was a sensational story: a young girl, sister to a clergyman, daughter of a park superintendent, described by her mother as "a strong girl, mentally clever, quick and clear". There was her young man, her strange indefinable relationship with a married man, her depression following the recent deaths in the family --- and her drinking. Florence Roger admitted that she and her sister both "were in the habit of taking spirits".

"Was it because you were out of health?" asked the coroner.

"I don't know!" wept Florence, saying they had been drinking for about two years and "it used to make us excitable at first, but depressed afterwards."

Fortunately for me, and less fortunately for Alexander Roger the Minister, one of the longest and most detailed accounts appeared in The Cardiff Times. Harriett Roger née Probert was heavily pregnant with her second child Cuthbert Wilfred when Alexander had to charge off to London for the family emergency.

Alexander attended the inquest, of course, as head of the family and to formally identify Jessie's body. He made a brief statement on the second day of the two-day proceeding: he had not "been home for eight or nine years, and really knew little of matters."

Several witness were called: the two chemists Jessie had visited on that last day, the doctor who attended her, her baffled brother Alexander, her devastated mother Elizabeth, grief-stricken sister Florence, and, most startling of all, her fiancé Arthur James Oakham --- the family didn't know that Jessie had been engaged for two years.

Oakham had a number of provocative things to say. He declared that Jessie had told him that she and Florence had gone out to dinner and the theatre with Willis (much to Oakham's displeasure), that Willis "had a vile temper" and "had knocked her down in the shop in Lower Belgrave Street " - presumably the flower shop that Florence was managing in 1889 with Jessie assisting. Oakham also told how Jessie locked herself away in her room (the newspapers differed on whether this was before or after her father's death in 1888), while Willis tried to force his way in. This story doesn't make a great deal of sense, as it is not clear why Mr. Willis would be at Era House.

Mr. Willis, the married dentist, gave testimony on the first day, saying he performed "little matters of business" for the sisters, and returned on the second day --- in the company of a barrister. He declared that he knew Florence as a friend, but that Jessie was "relatively strange to him" and denied any inappropriate behaviour. Athelstan Braxton Hicks assured him that "no one was accused here", but tore a strip off Willis in his closing statement, questioning his conduct with the Roger sisters, and telling him that the letters drafted for Jessie were "a tissue of lies". When Willis spoke up to object, his barrister quickly shushed him.

The inquest found that Jessie had committed suicide while in a state of unsound mind - a routine finding. The autopsy results indicated what the family doctor called pelvic peritonitis, which is usually caused by an inflammation of the fallopian tubes, and probably had caused Jessie enough pain to resort to laudanum for some time.*

The Chelsea Chronicle said only that the postmortem "revealed some important facts".

The Worcestershire Chronicle reported that "the evidence showed that the girl had fallen from virtue and had contracted a certain complaint."

The Derby Daily Telegraph declared that Jessie had "a horrible disease", and most papers had comments of a similar nature.

Given these events, you would probably think that I wasn't surprised to find Elizabeth Roger née Davis living in Lymington, Hampshire when the census was taken a year after Jessie's demise.

Fortunately for me, and less fortunately for Alexander Roger the Minister, one of the longest and most detailed accounts appeared in The Cardiff Times. Harriett Roger née Probert was heavily pregnant with her second child Cuthbert Wilfred when Alexander had to charge off to London for the family emergency.

Alexander attended the inquest, of course, as head of the family and to formally identify Jessie's body. He made a brief statement on the second day of the two-day proceeding: he had not "been home for eight or nine years, and really knew little of matters."

Several witness were called: the two chemists Jessie had visited on that last day, the doctor who attended her, her baffled brother Alexander, her devastated mother Elizabeth, grief-stricken sister Florence, and, most startling of all, her fiancé Arthur James Oakham --- the family didn't know that Jessie had been engaged for two years.

Oakham had a number of provocative things to say. He declared that Jessie had told him that she and Florence had gone out to dinner and the theatre with Willis (much to Oakham's displeasure), that Willis "had a vile temper" and "had knocked her down in the shop in Lower Belgrave Street " - presumably the flower shop that Florence was managing in 1889 with Jessie assisting. Oakham also told how Jessie locked herself away in her room (the newspapers differed on whether this was before or after her father's death in 1888), while Willis tried to force his way in. This story doesn't make a great deal of sense, as it is not clear why Mr. Willis would be at Era House.

Mr. Willis, the married dentist, gave testimony on the first day, saying he performed "little matters of business" for the sisters, and returned on the second day --- in the company of a barrister. He declared that he knew Florence as a friend, but that Jessie was "relatively strange to him" and denied any inappropriate behaviour. Athelstan Braxton Hicks assured him that "no one was accused here", but tore a strip off Willis in his closing statement, questioning his conduct with the Roger sisters, and telling him that the letters drafted for Jessie were "a tissue of lies". When Willis spoke up to object, his barrister quickly shushed him.

The inquest found that Jessie had committed suicide while in a state of unsound mind - a routine finding. The autopsy results indicated what the family doctor called pelvic peritonitis, which is usually caused by an inflammation of the fallopian tubes, and probably had caused Jessie enough pain to resort to laudanum for some time.*

The Chelsea Chronicle said only that the postmortem "revealed some important facts".

The Worcestershire Chronicle reported that "the evidence showed that the girl had fallen from virtue and had contracted a certain complaint."

The Derby Daily Telegraph declared that Jessie had "a horrible disease", and most papers had comments of a similar nature.

Given these events, you would probably think that I wasn't surprised to find Elizabeth Roger née Davis living in Lymington, Hampshire when the census was taken a year after Jessie's demise.

However, I didn't know what had happened to Jessie when I first encountered this census, and I was more curious and baffled about the seeming disappearance of Florence.

Every time I searched, the same record came up, but I didn't clue in.

Here's a Florence Roger, all right, but her birthplace is wrong. And look where she is! In a home for inebriate women all the way up in Yorkshire! Surely not!

Every time I searched, the same record came up, but I didn't clue in.

|

| You may click to enlarge this, and any other illustration. |

Eventually, I ordered Florence's death certificate.

Oh crud.

A home for inebriate women in Yorkshire. Sounds so grim, doesn't it?

Now, here again is where telling the story to someone else factors in. I knew I needed a visual for this presentation. Here's what I found.

First, a pdf document on the history of the area which turned out to be a Quaker community:

During 1886 a ‘Home for Inebriate Women’ was established in Mill Bank House, built

by Elihu Dickinson the Tanner. Initally many of the women came from the Manchester area. The list of fourteen patients in 1895 includes names of women from many parts of the country.

So I found Mill Bank by using StreetMap.co.uk for the details.

This is another sort of case where Google Maps isn't quite as helpful. Some odd place names, including this one.

So I went to Google Images and found a picture that fit in with my grim, Dickensian assumption of what such an institution would be like. Unfortunately, it was minuscule, and pixilated when enlarged.

About five years ago, I first encountered the handy tool called the "Google Search by Image". Has anyone used this? I've marked it with a garish pink square. You click on the little icon of a camera...

...then you can paste the url or, my preference, upload the image. (I just do a screen-save and upload that.)

I now have four more possibilities and look!

With the much enlarged and crystal-clear photograph, I could spot four details that I couldn't see when the picture was tiny:

the entrance, open and leading out to a pretty garden;

a little woman standing in the garden;

a croquet mallet, and a lawn covered with croquet hoops! (You may need to click on the image to enlarge it enough to see the hoops.)

Croquet and an open door -- suddenly the house doesn't seem quite so forbidding.

Perhaps Florence was simply too far-gone for even a gentle approach to help. Perhaps it did help, but she relapsed when returning home to her mother in Lymington.

I still wondered - why did Elizabeth relocate to Lymington, in particular? A part of the answer may lie here:

When Ancestry first introduced the Probate Calendar in 2010, this was one of my first discoveries. I finally knew what had become of Cuthbert. Now, of course, you can see the Probate notices for free at Find a Will and it's enormously easier to order a will through this web site.

I couldn't order a will for Cuthbert, because he didn't leave a will, this is an administration notice. An odd thing about the notice, it simply lists "Elizabeth Roger, widow". Normally, this would mean that Cuthbert left a widow. I have no evidence that he was married. I think this is his mother, who was now able to move into "Ivy Cottage" where Florence was to die three years later. I suspect the cottage may have belonged to Cuthbert. This is only a guess, for now.

The administration notice led me to Simonstown, South Africa.

Then the path led to this photo of Cuthbert's simple military grave at the Seaforth Old Burying Grounds, which lie at the foot of the steep hills overlooking the harbour on False Bay.

I carefully noted the name and email address of the volunteer who painstakingly photographed most of the graves and many other views of the cemetery, then sent her a profuse thank-you note, telling her how I was related to Cuthbert, and how grateful I was to know where he was. I still get an update on her work from time to time, which indicates to me that volunteers aren't thanked nearly enough.

Then, at Find My Past, a gem:

Cuthbert's full military record, which lists his promotions and ships, supplies me with his birthdate and tells me how he died.

Yet another victim of tuberculosis.

Three and a half years after nursing Florence through the final stages of tuberculosis and alcoholism, Elizabeth herself died, and Alexander the Minister found himself attending another inquest for a member of his family. This one was held because Elizabeth hadn't seen her doctor in a year, despite her rheumatism and shortness of breath.

My great-great-grandmother Elizabeth Roger née Davis: born to a poor agricultural labourer, sent at a young age into service, lost her youngest child as a toddler, had two sons die in another hemisphere, watched one daughter poison herself, and watched the other fade away slowly. Then, crippled with rheumatism, she took in boarders, and died after serving one of them breakfast. More than her fair share of disappointment and tragedy, I'd say.

This news article gives me a strong hint about where she and Alexander the Gardener are buried. There is a very famous cemetery at Woking, Surrey.

At one time, it was the largest cemetery in the world and boasted its own train service. Given Alexander the Minister's religious beliefs, I suspect that Alexander the Gardener and Elizabeth arrived at the Dissenter's Station at Brookwood Cemetery. I don't know what class their coffins would have travelled in, but Alexander the Minister was reasonably well off.

After a long career of stating his religious opinions vociferously, and resigning his Deputy Chaplain position at the Grand Orange Lodge of London for the same reason, Alexander Roger the Minister retired to a small seaside village called West Mersea.

by Elihu Dickinson the Tanner. Initally many of the women came from the Manchester area. The list of fourteen patients in 1895 includes names of women from many parts of the country.

So I found Mill Bank by using StreetMap.co.uk for the details.

|

About five years ago, I first encountered the handy tool called the "Google Search by Image". Has anyone used this? I've marked it with a garish pink square. You click on the little icon of a camera...

...then you can paste the url or, my preference, upload the image. (I just do a screen-save and upload that.)

I now have four more possibilities and look!

|

| This postcard reads: "Sanatorium, High Flatts, Nr Huddersfield" |

the entrance, open and leading out to a pretty garden;

a little woman standing in the garden;

a croquet mallet, and a lawn covered with croquet hoops! (You may need to click on the image to enlarge it enough to see the hoops.)

Croquet and an open door -- suddenly the house doesn't seem quite so forbidding.

Perhaps Florence was simply too far-gone for even a gentle approach to help. Perhaps it did help, but she relapsed when returning home to her mother in Lymington.

I still wondered - why did Elizabeth relocate to Lymington, in particular? A part of the answer may lie here:

When Ancestry first introduced the Probate Calendar in 2010, this was one of my first discoveries. I finally knew what had become of Cuthbert. Now, of course, you can see the Probate notices for free at Find a Will and it's enormously easier to order a will through this web site.

I couldn't order a will for Cuthbert, because he didn't leave a will, this is an administration notice. An odd thing about the notice, it simply lists "Elizabeth Roger, widow". Normally, this would mean that Cuthbert left a widow. I have no evidence that he was married. I think this is his mother, who was now able to move into "Ivy Cottage" where Florence was to die three years later. I suspect the cottage may have belonged to Cuthbert. This is only a guess, for now.

The administration notice led me to Simonstown, South Africa.

Then the path led to this photo of Cuthbert's simple military grave at the Seaforth Old Burying Grounds, which lie at the foot of the steep hills overlooking the harbour on False Bay.

I carefully noted the name and email address of the volunteer who painstakingly photographed most of the graves and many other views of the cemetery, then sent her a profuse thank-you note, telling her how I was related to Cuthbert, and how grateful I was to know where he was. I still get an update on her work from time to time, which indicates to me that volunteers aren't thanked nearly enough.

Then, at Find My Past, a gem:

Cuthbert's full military record, which lists his promotions and ships, supplies me with his birthdate and tells me how he died.

Yet another victim of tuberculosis.

|

| From the British Newspaper Archive at http://www.findmypast.co.uk |

My great-great-grandmother Elizabeth Roger née Davis: born to a poor agricultural labourer, sent at a young age into service, lost her youngest child as a toddler, had two sons die in another hemisphere, watched one daughter poison herself, and watched the other fade away slowly. Then, crippled with rheumatism, she took in boarders, and died after serving one of them breakfast. More than her fair share of disappointment and tragedy, I'd say.

This news article gives me a strong hint about where she and Alexander the Gardener are buried. There is a very famous cemetery at Woking, Surrey.

After a long career of stating his religious opinions vociferously, and resigning his Deputy Chaplain position at the Grand Orange Lodge of London for the same reason, Alexander Roger the Minister retired to a small seaside village called West Mersea.

Around the corner lived a retired builder's merchant contracter, also named Alexander. He had five daughters, the youngest of whom was single.

That's how my grandparents met.

Alexander died in 1933. Unlike his parents, all Alexander's children outlived him.

His will was very detailed, leaving generous legacies to his children, except one, whose spouse and children received a very complicated legacy in trust.

Guess from whom I'm descended.

So, the patterns of success and tragedy, of pride and disappointment, continued through the generations.

Like all families, really.

I still don't know why Florence Roger drank, or how Wilfred Roger ended up going to New Zealand. I don't know how Cuthbert got into naval engineering, nor who recommended that my great-grandfather go to Bancrofts Hospital School, and how he came to be so vehemently anti-Catholic. I still don't know -- not really -- why Jessie Roger drank laudanum on that fateful day in 1890.

I live in the hope that some day, I might come to know and understand, through the little details, through first-hand evidence, through taking pains, through not eliminating the improbable, through telling the story to others.

Thank you, Sherlock Holmes.

And thank you for letting me tell this story to you.

*After the presentation, I was approached by several BIFHSGO members, some with interesting theories on Jessie's situation. While many ideas had a certain amount of merit, I think Sherlock Holmes would refer them to his axioms, particularly the one about theorizing without sufficient data.

No comments:

Post a Comment